By Andrew Ormston

Drew Wylie Projects and Queen Margaret University

/CASE ANALYSIS

Diversity for sustainable development in cities and regions: two case studies from the Philippines

Creative hubs are increasingly attractive vehicles for pursuing diverse and sustainable development. Most of them started out in response to the particular needs of a group of creative organisations or professionals, but funders and public bodies have woken up to their potential for strategic interventions. However, the holistic and socially driven ethos of many creative hubs does not easily fit into the structures and mechanisms of national insitutions and governments. This paper discusses this dilemma informed by recent research recently carried out by the author, GJ Ouano-Saguisag and Jennifer Intac for the British Council in the Philippines, paying particular attention to two case studies, Pineapple Lab in Makati and Anthill Fabric Collective in Cebu.

The creative economy is growing in the Philippines with increased government and municipal interest. Strategy is not myopically focused on economic impact and competitiveness, but also addresses inclusion, sustainability, and creative city-making. This includes a focus on creative hubs, with a plethora of new hubs emerging over recent years.

“A creative hub is a place which brings creative people together. It is a convenor, providing space and support for networking, sustainability, and community engagement within the creative, cultural and tech sectors” (British Council, 2017, p. 42)

Stakeholders such as the Philippines Departments of Trade and Industry, muncipalities, universities and creative practitioners all recognize the growing contribution of creative hubs. They exhibit characteristics that are highly valued in a country whose creative economy is extremely vulnerable to variations in global trade, (“when the U.S catches a cold, we get influenza”[1]). The perception is that these MSMEs have a breadth of impact that nurtures resilience, such as the development of local markets and local employment that resists the pull of emigrant recruiters. As ever, one of the challenges facing enthusiasts in institutions arguing for increased investment and a louder voice for the creative sector lies in understanding what is going on and demonstrating its impact to colleagues and sponsors, who may be sceptical of businesses that attach as much importance to their community contribution as to their profit and loss account. Creative hubs can produce employment statistics but how do you demonstrate their contributions to places and people? Particularly when your audience is likely to include some of the ‘if you treasure it, measure it’ brigade that populate much of the public sector.

The situation is not helped by the lack of a unified universally agreed definition of creative economy, and the creative and cultural industries are missing standard statistical frameworks. There are also differing views as to what cultural assets are. Most politicians and officials understand the value of a museum, but some don’t grasp the more contemporary cultural chameleons that resist traditional categorisation. This includes many of the creative hubs that have expanded across the creative landscape. One approach with which funders have attempted to resolve this issue is by proposing typologies of creative hubs. In the Philippines a survey of 84 creative hubs that applied to the British Council’s Creative Innovators Program did produce clear clusters of activity, from provision of spaces, markets, training and new products to ‘softer’ impacts like quality of life, cultural preservation, innovation and resilience. The profile of hubs and their functionality also includes common traits. For example, most Filipino hubs have been operating for under 5 years and provide business support, collaborative opportunities, knowledge exchange, consultation, networking and mentoring. Creative hubs in the Philippines almost always attach as much importance to social and creative impacts as to economic ones when it comes to the local creative economy. The analysis revealed that:

- Hubs promote family and community resilience, enhancing family life and targeting groups experiencing challenges.

- Where the creative economy is not sufficiently developed to support fee levels and year-round income for artists that would support agency types of infrastructure, hubs directly support creative communities.

- Creative hubs also support a sense of place and cultural identity by promoting the quality of Filipino creative outputs and through providing more inclusive developmental models for local communities.

- They tend to adopt a holistic approach to inclusion, benefiting different generations and social groups in both urban and non-urban situations. Some hubs have the connecting up of urban resources and markets with rural creative communities at the heart of their mission.

- Environmental impact is a central issue for many hubs that are actively developing and mainstreaming new production approaches. Upcycling and innovative uses of traditional materials can be found in the work of many hubs.

However, creative hubs resist typologies as they are almost always unique, shaped by a cocktail comprising their scope, location, community, sub-sectors and trajectory. Our research observed this complexity in action across the work of over 12 hubs working across a number of sub-sectors.

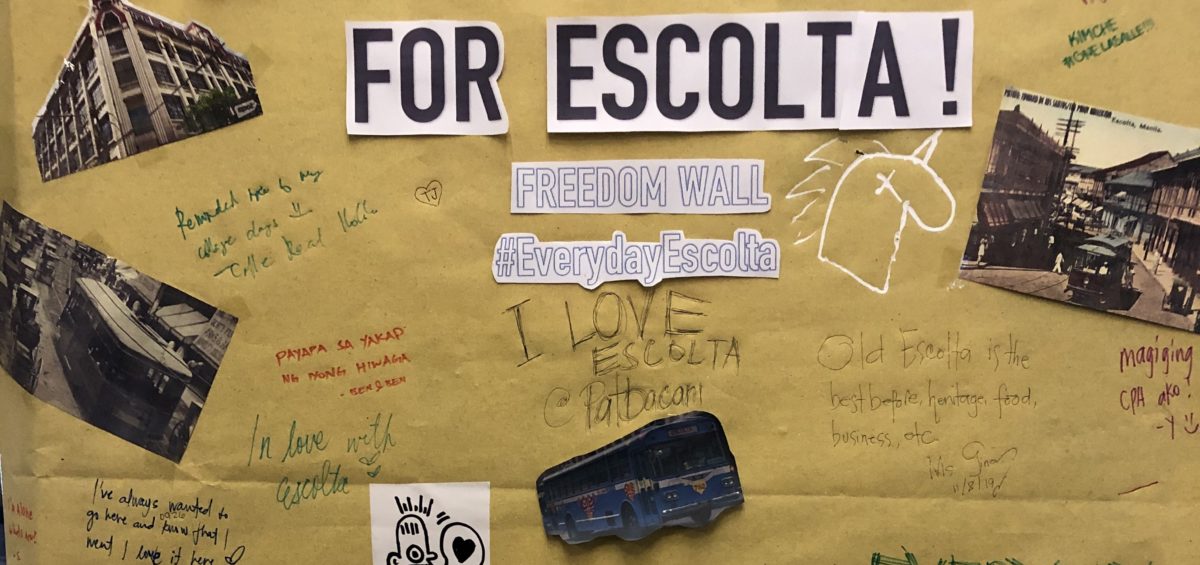

Hub: MakeLab is an artist-run initiative rooted in Escolta, Manila, which provides space for a new wave of Filipino creative entrepreneurs, enabling individuals to make the shift from “making a living” to “making as living”. Here the organisation’s development has been profoundly connected to the regeneration of Escolata, and provided an alternative model to gentrification that was embraced by other businesses in the area. Much of the areas’ original architecture is likely to remain intact, and by establishing a regular street market, the idea of public space has been reclaimed. In contrast, Purveyr is focused on brand and fostering a creative spirit in young people through stories, objects and experiences from the Philippines. The idea is to shift Filipino perspectives of their creative culture by engaging audiences and communities through digital, print, events and retail. The founder is showing how a focus on brand can both develop domestic markets and also the credibility of careers in the creative sector

The Philippines is an inherently creative place with music, visual arts and crafts constantly on tap. Yet this is not always fully appreciated as an asset for the country. Cebu Furniture Collective (CFIF) is direclty tackling the undervaluing of local furniture design and production, and a historic overdependence on international markets. Much of the world’s fashion furntiture is produced in Cebu, but is labelled as a foreign brand. CFIF tackle this through training, education, and advocacy linked to Cebu Design Week, which promotes the province’s furniture industry and works to make it relevant to contemporary markets. They are far from alone. Also in Cebu, HOLICOW supports the sustainability of the furniture sector based on the “kalibutan way” of emphasising the need to be concerned about the environment and giving value to every natural material they utilize. By developing new approaches to traditional materials like bamboo, and by putting upcycling at the centre of their work, they are creating a more sustainable sector and jobs for established furniture craftspeople that are thrown out of work when the international markets contract.

In Makati, Toon City Academy provides a pipeline for skilled animators for the animation industry, offering opportunities to people who might have minimal education and skills. This had an unexpected spillover effect as young people with a range of disabilities realised this offered them a potential route to employment. The Academy responded positively to this development and stimulated demand for training from students with special needs and from provinces where access to animation is limited. This has in turn directly led to their employment in the sector and an Academy ambition to develop capacity in less urbanized areas. CraftMNL also looks to create sustainable creative employment in the provinces and rural areas by empowering local makers and crafters, particularly those in the provinces. What began as an urban training base has developed into an agency that has supported the development of self-sufficient crafting communities in rural areas.

As it is the case in Europe, there has also been a rapid growth in co-working spaces in the Philippines, responding to an apparent limitless demand. The creative hub operator, A Space, first introduced the concept of co-working to the Philippines in 2011 and operates a co-working programme, providing space for events such as pop-up art galleries, craft workshops and film screenings. The organisation is expanding but is anxious to maintain a commitment to working with the creative communities in which its spaces are situated. In Cebu, this has contributed to a distinctive cluster of creative hubs that share facilities and capacity to maximise their impact as well as responding to peaks and troughs in their own activity.

As it can be seen, creative hubs are all distinctive and do not provide models that can be easily ‘lifted and shifted’ into other settings. However, they do share common values and processes that can be learnt from and even replicated by emerging organisations. Two in-depth case studies in the Philippines concern organisations that have recognised this potential and are each pursuing wider impacts using different approaches.

Pineapple Lab is a pioneering cultural organisation based in the emerging creative district of Poblacion in Metro Manila. The organisation’s reputation and influence cannot be underestimated and it has inspired many artists and creatives in the local community and beyond, with a reach into Asia, Europe and the Americas. Pineapple Lab has its roots in campaigning for LGBTQIA rights and the development of local artists. The team launched the now famous Manila Fringe, based on the founder’s experience with the New York Fringe, and they now operate a dynamic cultural centre which is playing a central role in shaping Poblacion as a creative district and evening economy. Work has extended into other sub-sectors, including workshops in underused cultural heritage buildings in the district.

The approach is based on a view that Manila is rich in creative talent but lacks the infrastructure to sustain professional development and market growth. Success is demonstrated in the number of artists attributing their professional careers to Pineapple Lab, their role in creating the strategy and commitment of the municipality, and links to diaspora markets and artists. During the research, we attended weekend workshops at a local museum where artists were at pains to point out that their careers had to a large extent been built on the opportunites afforded by work with Pineapple Lab. More surprisingly, we also met the Head of Arts for the municipality at the workshops, who talked about his interest in the sector developing through his volunteering with Pineapple Lab. This has resulted in Makati having the most dynamic approach to cultural strategy in Metro Manila, and in Pineapple Lab having a strong voice in its development.

Anthill Fabric Gallery is an equally inspiring organisation. The founder, Anya Lim, began from the determination that the rich culture of weaving she experienced as a child on trips around the Philippines would also be available to her children. It was founded using social enterprise approaches to cultural development and works across weaving communities throughout the Philippines, based on the Geddes principle of ‘think global, act local’. The organisation creates markets for high quality and creative weaves, both domestically and in the diaspora. It connects this with its work to raise the creative and business acumen of local weaving communities.

The values of the organisation mean that weavers can sustain community and family life in areas where economic emigration is endemic. Local women have viable options to work as weavers in their local community and have an active family life. They often live in communities where recruiters for domestic jobs abroad are most active. The creativity of communities of weavers is treated as a valuable asset in itself, with local weavers now working directly with fashion brands on developing new patterns and weaves. The most established weaver community is now able to work independently, creating capacity for Anthill to work with new groups.

The organisation demonstrates how social enterprise principles of development can effectively drive business growth and sustainabilty without compromising the values of an organisation. The quality and creativity of the work has created high value markets at home and also in diaspora communities around the world. Anthill organises pop-up fairs in cities like New York and Los Angeles, and is finding that Filipinos living abroad are enthusiastically responding to authentic weaves that are identified to particular weavers in particular communities.

Anthill is developing its social enterprise method and toolkit for its own use and in ways that could be employed by other creative hubs. This includes developing new methods of capturing social and cultural impacts of their work. An example of this approach being embedded at national level is the SenScot ‘Unlocking Potential’ cloud based took in Scotland, which is is designed to capture both hard and soft impacts.

It uses social capital as a framework under four headings:

- Networks comprise ‘bonding’ ties between members of community; ‘bridging’ peer-to-peer; and ‘linking’ vertically to influencers.

- Shared understanding reflects the shared norms and values impacting on shared standards of behaviour and expectations in the sector.

- Reciprocity is based on people supporting each other, confident that someone will return the favour in the future.

- Trust is the final element of the framework, with members of the community being honest and acting cooperatively.

In contrast to the social enterprise approach, cultural and creative policy frameworks can struggle to accommodate organisations like Pineapple Lab and Anthill. The complex and diversified character of the creative sector along with the prevalence of MSMEs has led to it being labelled as fragmented. This has sometimes undermined its investment case and the Philippines is no exception to this challenge. However, the problem has less to do with fragmentation and more with a mismatch. From the perspective of a creative hub, the institutional framework looks fragmented. An organisation that happily integrates economic, social, place-making and creative impacts looks at institutions clinging to their silos and sectoral demarcations and can turn away from the opportunities they offer. However, the preparedness of Makati municipalilty to work with Pineapple Lab at the level of policy and strategy, and the effectiveness of the social enterprise principles underpinning Anthill Fabric Gallery, show that there are pathways for funders and institutions to support and collaborate with creative hubs.

Any consideration of sustainable development has now to grapple with the impact of COVID-19 and the ambition of governments to ‘build back better’, removing the bureaucratic silos and sector demarcations that can create barriers for development at local level. Creative hubs have an emerging track record in bringing different players together for common purpose in localities and can be a valuable resource (even an anchor organisation in some instances), for mobilising local social and economic recovery.

Questions for further discussion

- How can the voice of smaller scale creative and cultural organisations be most effectively incorporated into policy development at municipal, national and regional level?

- Should funders invest in creative hubs as a community of practice, with funding for collaborative frameworks and resources?

- How can impact measures developed by creative hubs in response to their own priorities be used to influence funding organisations and policies?

References

BRITISH COUNCIL. (2017). Fostering Communities: The Creative Hubs’ Potential in the Philippines. British Council. Available at: https://www.britishcouncil.ph/sites/default/files/creative_hubs_report_-_ebook_0.pdf

ORMSTON, A., OUANO-SAGUISAG, G.J. AND INTAC, J. (2020). Happy Nests — The social impact of creative hubs in the Philippines. British Council. Available at: https://www.britishcouncil.ph/sites/default/files/british_council_-_happy_nests_-_full_report_pages.pdf

Biography

Andrew Ormston is founder of Drew Wylie Ltd., an international consultancy working across the cultural and creative industries. Recent projects have included work on creative hubs in SE Asia, film in Jordan, culture and societal impact for the EU, international arts policy comparisons for the Scottish Parliament, and municipal cultural policy. He is a Lead Expert for the EU, and an evaluation expert for the British Council and the Carnegie Trust. Andrew is a lecturer on the post-graduate cultural management course at Queen Margaret University. Recent publications include ‘Space to breath: nurturing an integrated heritage’, SCIRES-IT, 2019. Andrew is a Board member of the Queen’s Hall Concert Hall, Berwick Film & Media Arts Festival, and Scotland’s Regeneration Forum (SURF). Andrew holds a MSc in Environment, Culture & Society from Edinburgh University.

Andrew Ormston is founder of Drew Wylie Ltd., an international consultancy working across the cultural and creative industries. Recent projects have included work on creative hubs in SE Asia, film in Jordan, culture and societal impact for the EU, international arts policy comparisons for the Scottish Parliament, and municipal cultural policy. He is a Lead Expert for the EU, and an evaluation expert for the British Council and the Carnegie Trust. Andrew is a lecturer on the post-graduate cultural management course at Queen Margaret University. Recent publications include ‘Space to breath: nurturing an integrated heritage’, SCIRES-IT, 2019. Andrew is a Board member of the Queen’s Hall Concert Hall, Berwick Film & Media Arts Festival, and Scotland’s Regeneration Forum (SURF). Andrew holds a MSc in Environment, Culture & Society from Edinburgh University.

[1] The phrase “when the U.S catches a cold, we get influenza” is a common phrase describing the dramatic impact that downturns in the global economy have on Cebu’s creative industries, and particularly furniture producers.